Estimating the prevalence of code sharing in scientific research

July 19, 2018

Science and scientific peer review are often superficially assumed to be rigorous, particularly by non-scientists. Therefore, it’s strange that it’s not standard practice to share all code and data needed to reproduce scientific publications. This is pretty troubling, as I’ve found significant bugs in my scripts in the late stages of my analysis soon before submitting to peer review, and I doubt I’m in a small minority here. I worry that someone will find a bug in our shared code that would warrant a retraction. This is an understandable reason why many aren’t so inclined to make their code and data easily accessible. Regardless, transparent code sharing is the right thing to do, and so I was curious in quantifying how often code is in fact shared (see code).

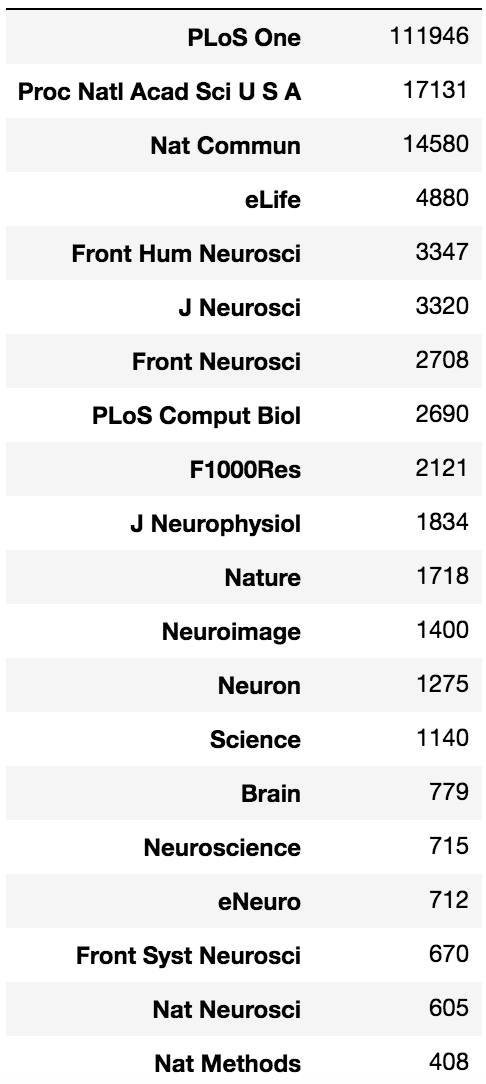

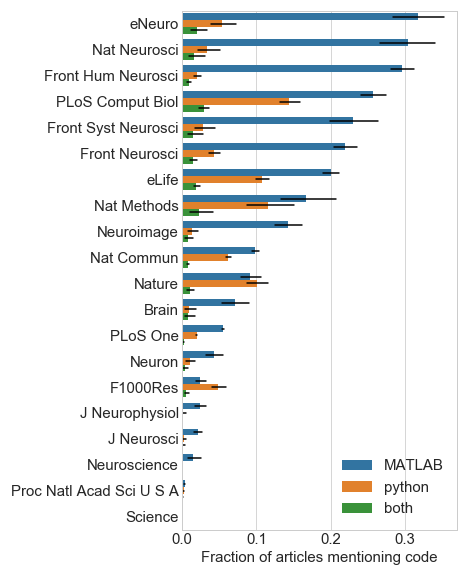

To do this, I scraped the full text of 173,979 papers published since 2014 from 20 journals (see counts in table at bottom). I then approximately determined the subset of these papers that wrote custom software by narrowing the analysis only to papers that contained the strings “matlab” or “python” (Figure 1).

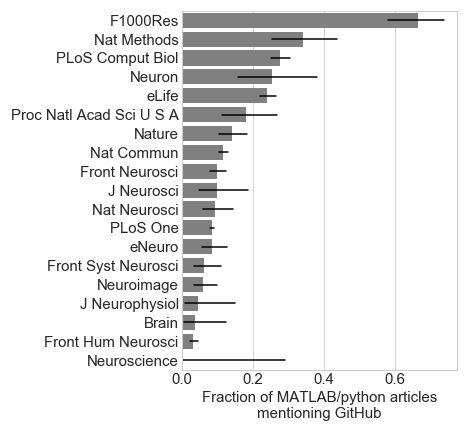

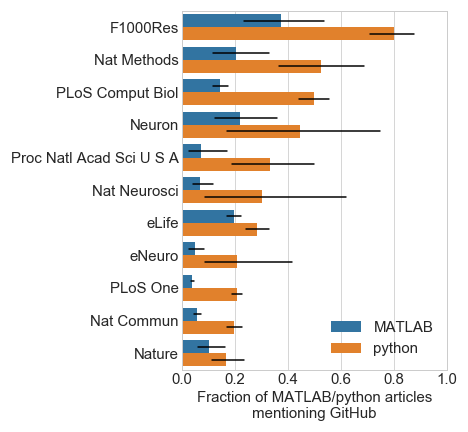

My first-pass estimate for code sharing was checking if “github” appeared in the paper text. Using this estimate, Figure 2 shows considerable variance across journals (Figure 2).

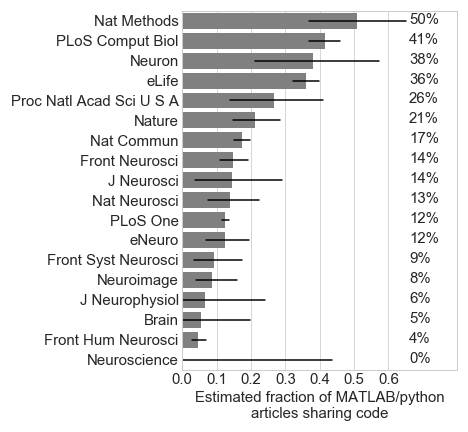

In order to assess how accurate the “github” surrogate is for code sharing, text surrounding the keywords “github”, “open”, “code”, “matlab”, and “python” were extracted from the 200 putative MATLAB/python articles in PNAS and Nature Methods. I then wrote a script to loop through all of this extracted text and label each article as sharing code or not (googling the articles when clarification was necessary). Nearly all of the “github” articles were confirmed to share code (52/53), and 29 articles shared code outside of GitHub. Therefore, to estimate the prevalence of code sharing in Figure 3, I increased the number of articles containing “github” by 50%.

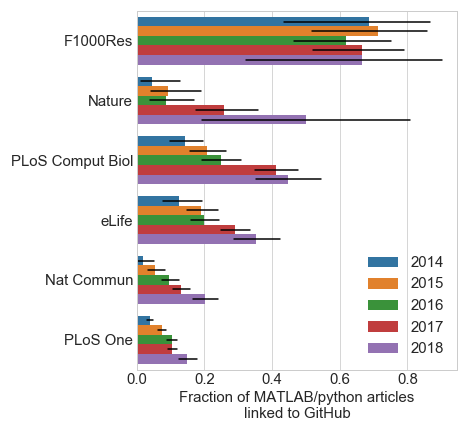

I fully acknowledge that this is an imperfect estimate of code sharing, but it seems a reasonable compromise given limitations in time and NLP. I further found that python researchers were more likely to share code via GitHub compared to MATLAB researchers (Figure 4), and code sharing has been increasing steadily each year since 2014 (Figure 5).

It’s interesting to see how the different journals stack up in terms of code sharing. Especially since some of these (Nature family, PNAS) require statements of code / data availability. However, a recent study showed that less than half of authors (of 2011-2012 Science articles) fulfilled requests for code and data sharing Stodden et al., PNAS, 2018. Due to its automation, this current analysis allowed a broader scope, though of course has its share of limitations. In the future, I’m hoping to expand this to study data sharing across fields and institutions (this data is already scraped with the current code). If anyone else is interested in working on this, I’ll happily send you the data already scraped.