Brain Oscillations and the importance of waveform shape

January 05, 2017

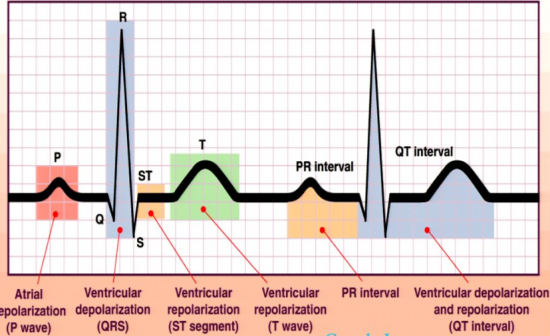

The Nobel Prize winning method of recording the electrocardiogram (ECG), and associated discovery of the PQRST complex in the ECG signal, resulted in a significant shift in the understanding of cardiac physiology. Once the ECG was demonstrated, researchers began to focus on identifying the physiological generators for each of the temporal subcomponents of the PQRST complex. These subcomponents, which include the slower P- and T-waves along with the sharper QRS complex, were hypothesized to reflect different aspects of cardiac electrophysiology (see Figure below). In fact, it was the careful consideration of how these complexes were generated that guided discoveries of new cardiac cell types and their interactions, in turn leading to a better understanding of the physiological origins of cardiac disease, reflected by abnormalities in the ECG signal.

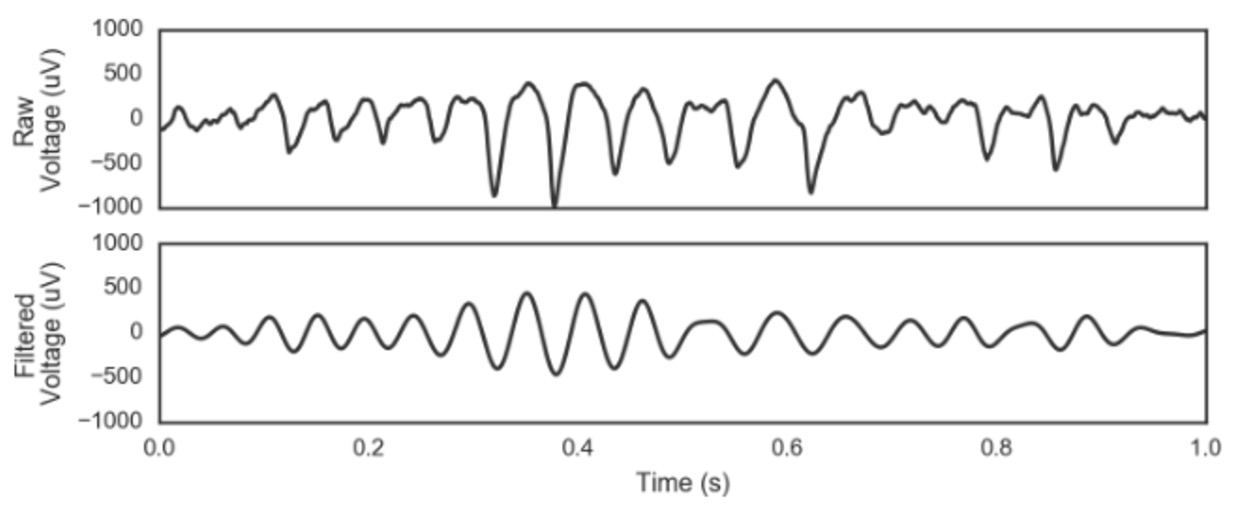

In contrast to the physiologically-oriented consideration of the rhythmic ECG, analysis of the rhythmic electroencephalogram (EEG) tends to be technique-oriented. This may be because oscillations in the EEG are less stereotyped than those in the ECG, and so waveform analysis is more challenging. Therefore, neural signals are usually filtered in canonical frequency bands to analyze rhythms including delta (1-4 Hz), theta (4-8 Hz), alpha (8-12 Hz), beta (15-30 Hz), gamma (30-90 Hz), and high gamma (>50 Hz). This narrowband filtering inherently assumes that the oscillation of interest is sinusoidal. However, our review discussed how neural oscillations in raw data are often nonsinusoidal, and so filtering distorts their properties (see Figure below). The bottom oscillation is what happens to the brain data above it after it’s been filtered. Note how the filter smooths out the “peakedness” of the real data, forcing it to become more like a pure sine wave.

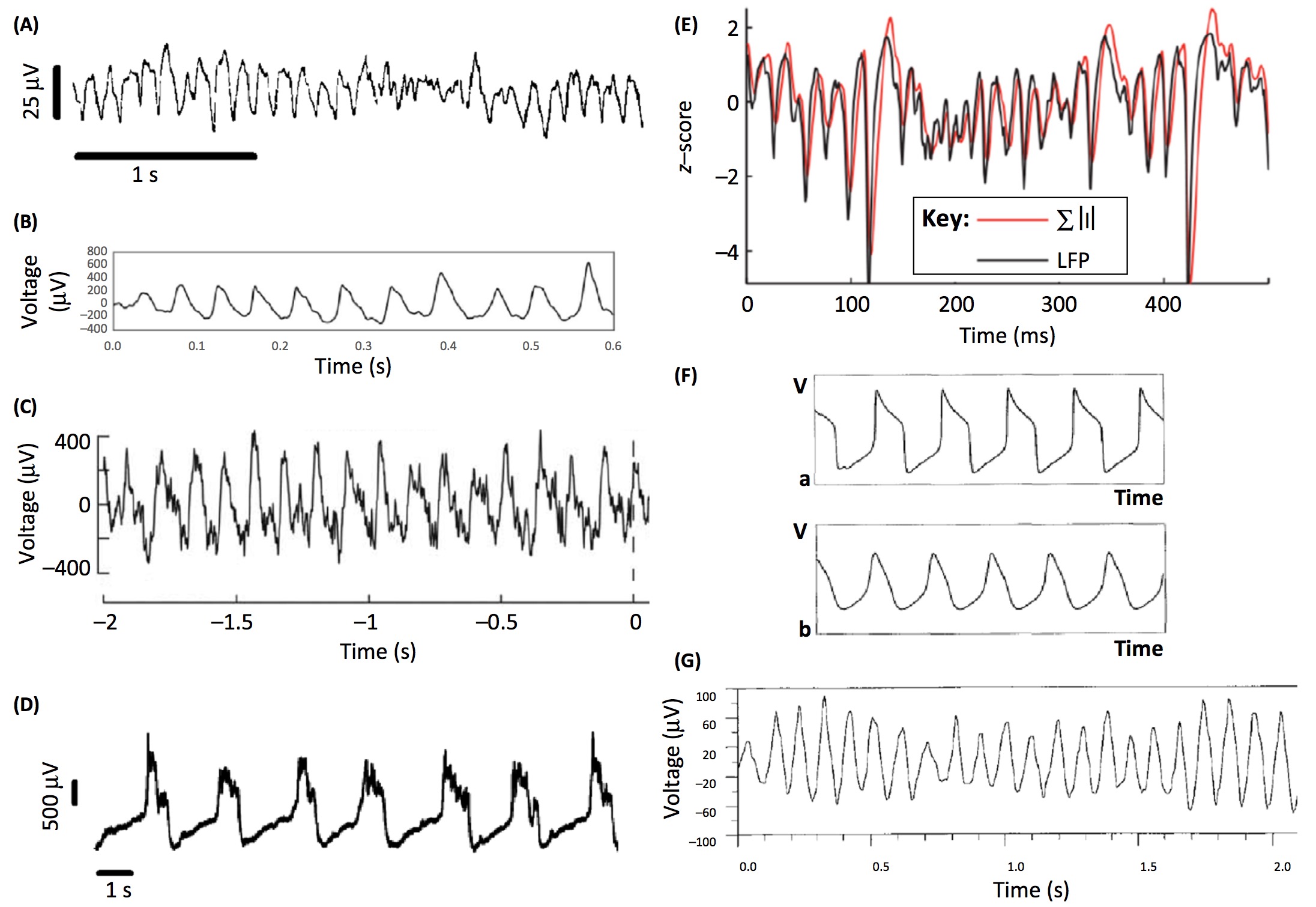

The fact that nonsinusoidal oscillations confound widespread analyses of oscillatory phase and amplitude has become a popular topic recently, leading to at least 6 papers on this topic in 2016 [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6] This is important to consider, as neural oscillations are very often nonsinusoidal (see Figure below).

In our recent review in Trends in Cognitive Sciences, we address this inconsistency between standard practice (use of a sinusoidal basis) and the shapes of the oscillatory waveforms in our data (diverse and frequently nonsinusoidal). Perhaps measuring the shapes of the oscillatory waveforms in our data will provide us with more information about the biophysical underpinnings of these oscillations. By way of analogy, one can imagine that if a computationally efficient Fourier transform method existed when the ECG was first being investigated in the 1920s, the researchers might have instead (inappropriately) fixated on cardiac oscillations, phase-amplitude coupling, and so on. This would have been at the detriment of the discovery of fundamental cardiac physiology and pathology that arose because of careful consideration of the time-domain PQRST complexes.

Our review supports the case that the temporal dynamics of neural oscillations carry critical biophysical information. We outline multiple lines of reasoning that point to this conclusion:

- Brain rhythms are different shapes in different brain regions. Perhaps this reflects differences in neural computation, despite sharing a common fundamental frequency (see panel A below). [Buzsaki et al. 1986]

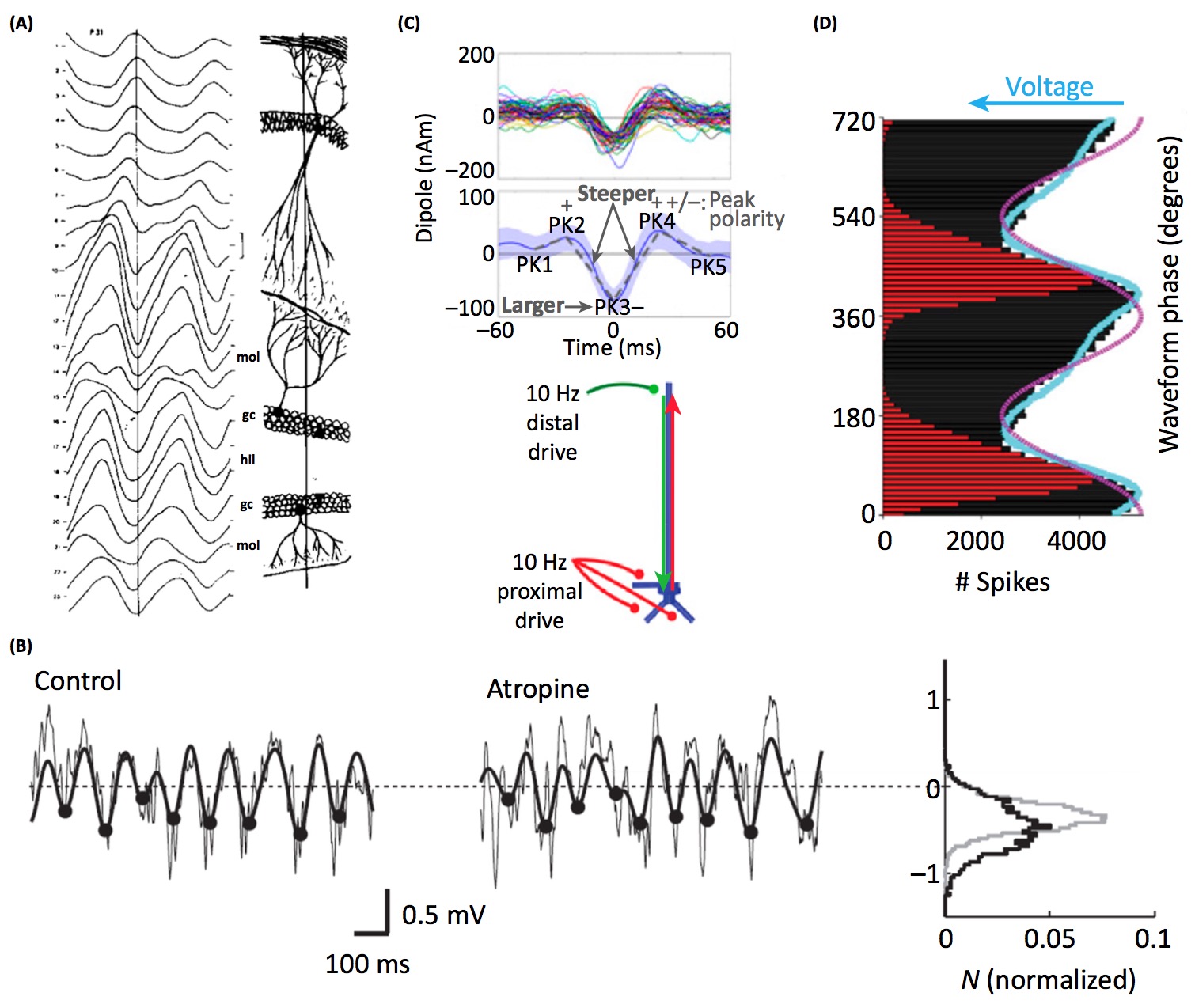

- Manipulating the concentration of neurotransmitters modifies features of oscillatory waveforms. Perhaps the waveform shape of some oscillators reflect properties of neuromodulation (see panel B below). [Hentschke et al. 2007]

- Cortical beta oscillations have a stereotyped waveform. The waveform properties are predicted by a model of synchronous distal and proximal excitatory synaptic synchrony (see panel C below). [Sherman et al. 2016]

- The sawtooth-like waveform of hippocampal theta oscillations fits the firing rate histogram of the local neurons better than a sinusoid. Perhaps the waveform shape of some oscillators reflect the temporal properties of local spiking (see panel D below). [Belluscio et al. 2012]

- Motor cortical beta oscillations are sharper in untreated patients with Parkinson’s disease. Perhaps this reflects hypersynchronization of the beta generator. Perhaps waveform shape may be a useful biomarker for disease. [Cole et al. 2016]

- Hippocampal theta oscillations are more asymmetric while a rat is running compared to during immobility, REM sleep, or lever pressing [Belluscio et al. 2012]. Hippocampal theta oscillations are also more asymmetric during an experience which a rat subsequently remembers [Trimper et al. 2014]. Perhaps changes in oscillatory waveform reflects a change in the mode of neural computation.

- Rhythmic electrical stimulation has different effects depending on the shape of the stimulating waveform. Most notably, electroconvulsive therapy is more effective using a rectangular waveform compared to a sinusoidal waveform. [Weiner et al. 1986]

While these lines of evidence do indicate that the shape of oscillatory waveforms is important, these observations are incredibly sparse in the current literature, and were previously unconnected to one another. We think that concerted analysis into the biological and behavioral correlates of waveform shape features will be fruitful to gaining more information from neural signals. Measures of waveform symmetry can become a part of our standard toolkit along with oscillatory phase and amplitude. We have a public code repository on GitHub for analyzing some features of waveform shape. In the coming years, we hope to gain an improved understanding of what waveform shape reflects about the generators of neural oscillations.

*This post initially appeard on our lab webpage