Game theory to guess closest random number

June 14, 2015

See IPython Notebook for this post here. (now runs with binder!)

It was an exciting day when the first external monitor arrived in the Voytek lab. It was a big, beautiful ASuS. But there was one problem: there were 4 graduate students. And they all wanted that monitor. Fortunately, our cherished post doc had the solution: he would generate a random number between 1 and 100 billion, and whoever guessed closest would win the monitor.

He came back in the room with some billions written on a piece of paper and waited for us to start guessing, aloud. But no one wanted to be the first to guess. I thought I would be at a disadvantage if the others had knowledge of my guess when they were formulating theirs. For example, Nicole ended up betting 3, followed by Torben who bet 4, so Nicole got completely shafted. I waited until Tom and Richard guessed their numbers and then realized, oh shit, guessing last actually put me at a disadvantage! I was embarrassed at my incredibly mediocre game theoretic strategy, so here, I attempt to establish what the best strategy would have been for this game.

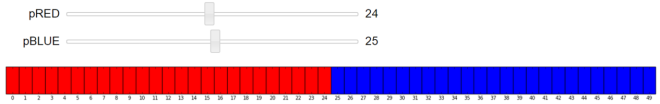

Let’s start with a simple case, in which there are 2 guessers (P1 and P2) and they are guessing a uniform random integer in the range [0,49]. We are interested in how the two players should bet in order to maximize their individual probabilities of winning an external monitor. In order to maximize its probability of winning, P2 should choose a number adjacent to the guess of P1. Specifically, P2 should guess 1 below P1’s bet if it was above the median of the distribution (24.5), and 1 above P1’s bet if it was below the median. Therefore, P1 should always bet 24 or 25 so that P2 cannot control more than half of the numbers.

Figure 1. Results of a strategically played 2-player guessing game. The sliders indicate the numeric guesses for the two players (pRED and pBLUE). The number line indicates the numbers controlled by pRED and pBLUE. Gray rectangles (absent in this screenshot) indicate numbers that are equidistant to both bets, and thus neither player wins. Figure is interactive in the IPython notebook corresponding to this post in which the bets of pRED and pBLUE can be adjusted on the sliders and the range of integers can be adjusted in the script. pRED = P1; pBLUE = P2.

While this optimal solution can be arrived at intuitively, the best strategy becomes less clear when the number of players in the game is increased. Therefore, I developed a brute-force algorithm to identify the optimal guesses to be made by up to 4 players (assuming that the sole goal of all players is to maximize their probability of winning). Specifically, for the 3-player scenario, I calculated the numbers controlled by each player for every possible combination of bets. For each potential bet by P1, I calculated the optimal bet by P2 that would result in the maximal probability of winning, applying a rationality assumption for P3 similar to the intuition explained in the 2-player scenario above. P1’s bet was then determined by choosing the number that maximizes its probability of winning, using the predicted bets by P2 and P3.

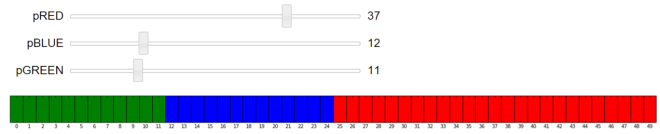

Figure 2. Results of a strategically played 3-player guessing game. Same conventions as previous figure. Note that the optimal bets for P1 and P2 lie at the 1st and 3rd quartiles of the distribution. This will be true for any random distribution chosen, but its proof is beyond the scope of this post. pRED = P1; pBLUE = P2; pGREEN = P3.

I was shocked to see the results of this experiment, which indicated that P1 had the highest chances of winning the game when betting was done strategically. This is counterintuitive because P2 and P3 make their bets with knowledge of P1’s bet, while P1’s bet is uninformed by that of P2 or P3. So is it the best strategy to guess first?

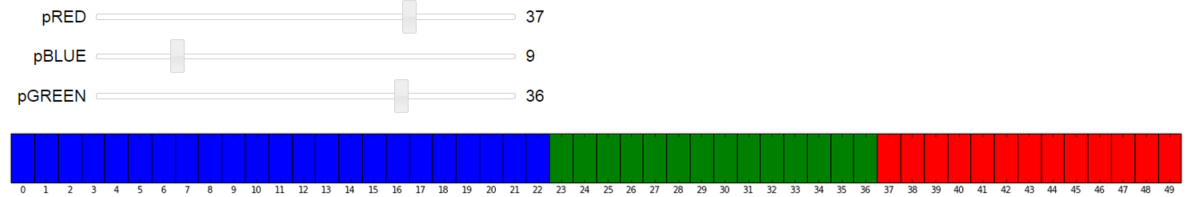

Well, it’s more complicated. There are situations in which players can use arbitrary discretion on their bets because multiple bets will result in the same coverage of the distribution. For example, P3 placed different bets in Figures 2 and 3 based on the same bets by P1 and P2 because either (and several more bets) yielded equivalent probabilities of winning for P3. The key difference between these two situations is their impact on the chances for P1 and P2.

Figure 3. Alternative results of a strategically played 3-player guessing game compared to the previous figure. In this case, pGREEN likes pBLUE more than pRED (i.e. the guess by pGREEN decreased the range secured by pRED more than that by pBLUE). In Figure 2, pGREEN liked pRED more than pBLUE (i.e. the guess by pGREEN decreased the range secured by pBLUE while not affected that of pRED). pRED = P1; pBLUE = P2; pGREEN = P3.

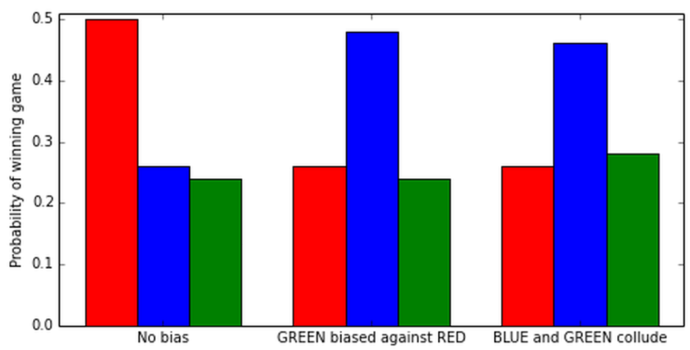

Because of this, I assert that it is best to be P2 in this game. P2 could strike a deal with P3 to allow P3 a slightly higher chance of winning if P3 promises to disproportionately interfere with P1’s bet (Figure 3). For example, Figure 4 shows that P2 may bet 9 on the condition that P3 bets 36. In this situation, P1’s distribution coverage decreases (from 25 to 13 numbers), P2’s distribution coverage increases dramatically (from 13 to 23), and P3’s distribution coverage increases marginally (from 12 to 14). pRED = P1; pBLUE = P2; pGREEN = P3.

Figure 4. 3-player guessing game in which pBLUE and pGREEN collude to maximize their probabilities of winning at the expense of pRED.

Figure 5. Changes in each player’s probability of winning with preferences and collusions of P3. RED = P1; BLUE = P2; GREEN = P3.

The last scenario I modeled is the case of 4 players (this final simulation took several minutes to run and the code would just get even more messy when adding more players). The original strategic output of this scenario is shown in Figure 6. These bets involve no collusion but rather are biased by the fact that np.argmax() returns the index of the first entry that is equal to the maximum value of the array. However, P3 and P4 can collude to maximize their combined probability of winning. Specifically, Figure 7 shows that one player bets in between P1 and P2 to decrease their coverage, while the other player can dominate the lower half of the distribution.

Figure 6. Results of a strategically played 4-player guessing game. Same conventions used as above. pRED = P1; pBLUE = P2; pGREEN = P3; pYELLOW = P4.

Figure 7. 4-player guessing game in which pGREEN and pYELLOW collude for the benefit of pYELLOW and pRED and at the expense of pBLUE. Note that any bet by pGREEN in the range [25,40] yields a coverage of 8 numbers for pGREEN.

In conclusion, we have observed that the optimal strategy for this guessing game is dependent on the number of players involved.

- 2 players: P1 gains a slight edge if the integer space contains an odd number of integers.

- 3 players: P2 colludes with P3 to maximize its probability of winning

- 4 players: P4 colludes with P3 to maximize its probability of winning

Any rule to how to optimally bet is not evident in this brute-force analysis of 2-4 players. Therefore, more clever analytics and/or more computational power are needed to define the optimal general strategy for this guessing game.