Median estimation is superior to random number generation in guessing game

May 25, 2015

See the IPython Notebook of the simulations in this blog post here (now runs with binder!)

I’ve been watching a ton of Numberphile lately. They continually blow my mind with some crazy series of numbers (Lucas numbers) or something so seemingly counterintuitive until the host unravels the puzzle to make it all make sense.

In this post, I was inspired by a recent Numberphile episode, How to win a guessing game. In this game, there are two players. Player 1 chooses two random numbers (A and B). Player 2 sees one of the numbers (A) and guesses if it is greater than or less than the other number (B). According to Alex Bellos, the host of this Numberphile episode, Player 2 gains an edge in the guessing game simply by generating a random number (K) of its1 own and using the following rule:

if K > A: guess B > A; else2: guess B < A

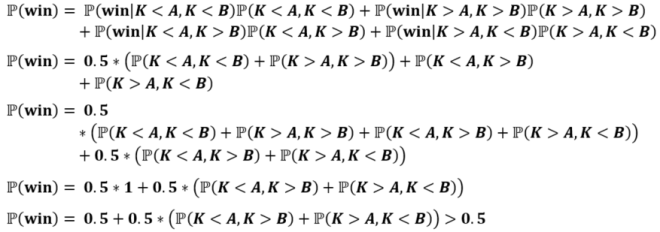

Naively, it would seem as if Player 2 has a 50% chance of guessing correctly, as K is independent of A and B. Alex goes through a proof by induction in the video, but here’s a formal one just for funsies:

At the end of the video, Alex mentions that he hasn’t run the simulation, but he believes that if Player 1 randomly chooses numbers between 10 and 50, then Player 2 will perform significantly above chance in a game of 100 trials. By assuming that Player 2 happens to know the distribution that Player 1 is using to generate A and B, my simulation confirms this (p < 10-5), binomial test). When running the simulation for 10,000 trials, it was found that Player 2 won about 67% of the time.

Figure 1. Generating random numbers to make a guess results in performance significantly above chance in just 100 trials.

However, there is a much better strategy. And it is less computationally expensive than repeatedly generating random numbers. Specifically, Player 2 should choose the value of K to be equal to the median of the distribution that Player 1 is using to generate A and B. Why the median? This is because A and B in this problem are independently taken from the same distribution. Therefore, if the median of the distribution is less than A, then it is more probable that a number (B) taken independently from the distribution will be less than A. This assumption, however falls apart when you consider that the human that generates A and B may intentionally generate them so that they are not independent.

Figure 2. Guessing performance can be improved just by choosing the same value of K on every trial. This is maximized (77% accuracy) when K is the median of the distribution used to generate A and B (68% accuracy when K is randomly generated).

But here’s a much more interesting question: in which situation is Player 2 more accurate?

- It has knowledge of the distribution used to generate A and B and generates K from randomly sampling from this distribution

- It has no knowledge of the distribution but rather generates K by estimating the median over time.

Unfortunately, I could not find an online data set for human-generated random numbers (though this paper has good methodology for doing so). Therefore, I generated 100 questionable random numbers of my own3 to run this experiment. Even more questionable, I artificially expanded the data set by generating new random samples with multiplication and division of current samples so that I could run over 10,000 trials. The simulations I ran with these random numbers showed that the median estimation strategy is more accurate, despite lacking the knowledge of the distribution used to generate A and B.

Figure 3. Median estimation is significantly more accurate than randomly generating K. This is the case even with a small number of trials (<100). The accuracy of the median strategy is about 76% after 100 trials whereas the random number generator strategy is only about 67% accurate.

With or without a priori knowledge of the distribution used to generate A and B, estimating the median yields higher accuracy than generating random numbers. Rather, the technique of estimating the median is slowly aggregating knowledge of the distribution that generates A and B.

However, and most importantly: this advantage is completely extinguished if A and B are chosen in a certain way that removes their independence from one another. In the final experiment I ran, the distribution I used to generate A and B differs from trial to trial. Specifically, B is generated by either randomly adding or subtracting 1 from A (e.g. trial 1: A=473, B=472; trial 2: A=-27, B=-26). Therefore, these samples are not independent. And so the median no longer carries any information of the probability distribution from which B is calculated. As expected, the accuracy of the two strategies plummeted (50.1% for random K, and 50.5% for median estimate) and were not significantly different from chance levels. This is proven intuitively by framing the situation this way: Knowing A and defining B = A + C, where C’s sign is random, it is impossible to guess above chance if B > A.

In summary, I have expanded upon Alex’s claims in the Numberphile video, suggested a new method for guessing whether B is greater than or less than A, and showed that if B is randomly derived from A (as opposed to an independent sample from the same distribution), then both strategies fall apart. In this case, no strategy exists that would allow the guesser to perform above 50% accuracy.

There are a few other aspects of this guessing game problem that are interesting. Maybe topics of future posts.

- What type of distribution used to generate K results in the greatest accuracy? For what distributions of A and B?

- Alex suggests using a (normal) random number generator, but I think that pulling numbers out of your ass would work just as well.

- What other strategies can be developed that are superior to median estimation?

- Finite random number generation biases guessing game

- You cannot sample from an infinite distribution of all numbers because this would take an infinite amount of time.

- If the random number generator of K has fewer bits than the generator of A and B, it cannot achieve >50% accuracy for certain strategic choices of A and B.

- This is kind of alluded to in the episode “The mathematical small print is that I need to take it from a distribution that covers all of the numbers…” (2:22)

- In the video, Alex says something like “the wider the gap between numbers, the wider the goal.” But we only consider [-1000,1000] to be a large gap because we encode numbers with a reference on the order of 1. Encoding “very large” or “very small” numbers requires more bits in our computers and more energy in our brains (though we do take advantage of patterns, so 111,111,111 is easier to remember than 497,283)

1I’m going to assume the players are animals so I don’t have to decide between: 1) the gender of the player; 2) repeatedly typing “his/her”; 3) being gramatically incorrect by typing “their.”

2When K was randomly generated, K was regenerated if A == K. When K was chosen as the median of the distribution, guess A < B if A == K.

3Generating random numbers was super exhausting. My human-generated random numbers obviously have some limitations. I set an arbitrary limit of 1000 on my numbers. It’s a small sample size. The samples are far from independent from one another. Though, this would be the case for all humans.